Or a Plea for Change

by Joana Sarah Grah

Do you still come across the common stereotypes against mathematicians in general and women mathematicians specifically? Maths is boring, maths is for loners, maths is unsexy (and done by unsexy people – I just stumbled upon this again recently when reading a quote-retweet by Hannah Fry replying to someone who claimed there are no “hot” people that are good at maths – just for the record, I know quite a few), maths is dry and above all – maths is for men!

I don’t know about you but I’m so tired of it. When did we exactly start to think that being good at a subject at school is something to be made fun of or to be ashamed of? I have heard this so many times: “Oh, I’ve always hated maths.”, “Only geeks and losers like maths.”, “I always sucked at maths.”. But in a – you know – kind of proud way? What’s wrong? Do you like not being able to calculate the appropriate tip when you’re eating out? Do you enjoy not understanding probabilities, hence not being able to evaluate risks for instance? Did you never see the exponential growth of infections during the pandemic – which has always been exponential in the first place – coming? It’s always easier to deny things we don’t understand but are afraid of. In the current situation this is particularly dangerous and even probably harmful for others. Nothing to be proud of if you ask me.

A solid foundational education in mathematics is essential, no doubt. But maths is so much more than being good at calculating stuff. In fact, I couldn’t name any area of application where maths doesn’t play a role. Natural sciences like physics, chemistry and biology, earth sciences, astronomy, medicine, economics, arts restoration – those are just some examples that come immediately to mind. The variety of mathematical fields and the respective methods is similarly vast – there’s so much to explore and really something to be passionate about for everyone. In addition, maths is absolutely no discipline where teamwork isn’t encouraged. In fact, you discuss and brainstorm with colleagues day-to-day (although there are exceptions of course). Interdisciplinarity is key to most problems and projects arising in applied maths.

Now let’s get to the point that bothers me the most and that is the reason we set up this webpage. Unfortunately, it’s still a common misperception that maths is not for women. Pretty pathetic given that we’re living in 2021 you ask? Yes, absolutely, but it turns out we’re still living in a patriarchy. That is why we need to be feminists.

At the beginning of your studies, you probably won’t realise the disproportion between women and men in maths. You’ll notice that you have very few or even no women professors. Most of the academic staff is likely to be men. The gap becomes more obvious the further you get. Finding women working in the same field at conferences is probably much more difficult than finding men. Seeing women on discussion panels and giving talks will be the exception rather than the norm. It is getting a bit better though and many people are aware of the problem and encourage diversity. Yet the majority of women seem to decide at some point of their academic career that they don’t want to pursue it further. Why is that? Anti-feminists, mostly men, often claim that it’s their personal choice to leave because they prefer a part-time job, a job in a less competitive environment, a job that fits their “abilities” and “interests” more, because they want to have a family and won’t be able to have children and an academic career. Nothing wrong about any of this but the crucial point is having the choice. It is indeed possible to both have a family and a professorship. And it is indeed possible to be a professor while still prioritising your leisure time, your mental health, your family, your friends. Not all women are given those opportunities. Most women don’t have the choice. It is a structural problem, an institutional problem, a societal problem. Maybe you missed the important discussions because you left an informal meeting after a conference day, as you were the only woman and felt uncomfortable, or because you didn’t have childcare for the whole night. Maybe you risk a huge fight with your family, or even ending the contact altogether, or you lose a relationship, because you’re spending too much time writing grants (instead of attending family events, going on your long-planned vacation or caring for your kids – or having kids). Maybe all the people in power making decisions are men and they like to surround themselves with like-minded men.

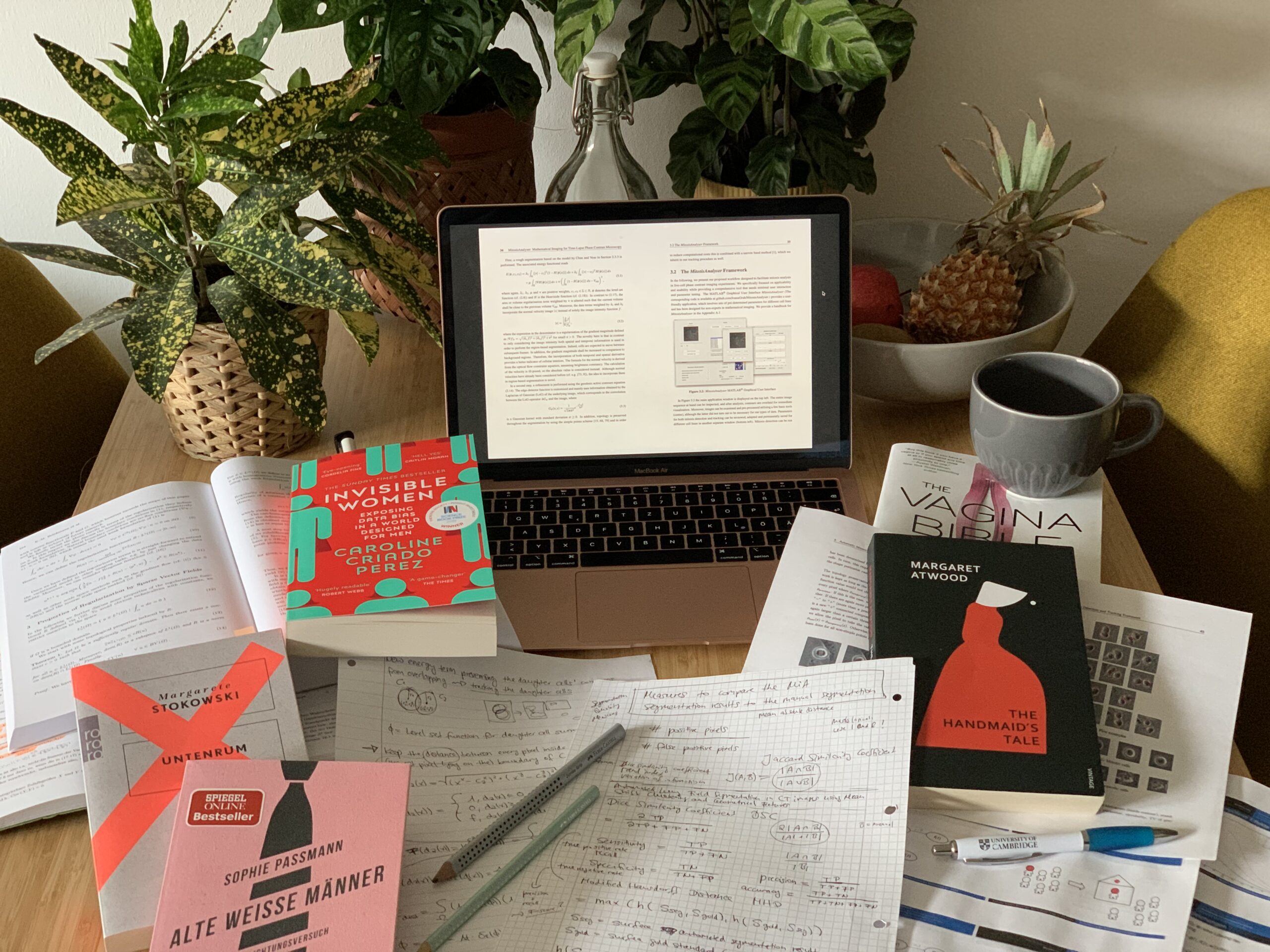

We need to make women in maths visible for the next generation who are desperately searching for role models because they don’t see them. We need to amplify the voices of women in maths because oftentimes the voices of men in maths are much louder. We need to showcase the variety and – more often than not – non-linearity of career paths including failures, doubts, setbacks, maybe starting all over again, maybe changing fields completely, maybe having children. We need to raise awareness for the lack of resources in schools and universities to highlight women in mathematics, for the fact that mental health is actually physical health and just as important as making sure you stay up-to-date with the literature and back up your work regularly. We need to normalise not working crazy hours on a regular basis, having a family, not having a family, admitting that you don’t know something, asking “stupid” questions (I know it’s stale but there really are no stupid questions, most of the time those are the important questions to ask) and having interests that have nothing to do with maths.

Why do I write this now rather than at the time when we launched our page at the beginning of the year? Because I was afraid I would sound too aggressive, I would probably exaggerate things and because I’m sharing very private opinions and experiences. On the other hand, it was about time. I reflected a lot about this recently and realised how much of it I suppressed or dismissed as innocuous. What really fuelled my anger was when I saw injustices happening to other women, to friends, to the next generation. Most of the time they seem subtle but they do impact your day-to-day work life significantly. I experienced women suffering from imposter syndrome that came across so strong and confident yet still being at the mercy of the broken system and socially acceptable misogyny. Besides the structural problem, there is the everyday sexism all of us are familiar with. Do you find it hard to literally be heard in a discussion? Do you have to raise your voice a bit extra? I certainly had to sometimes. Another classic is when a man paraphrases something you just said and gets all the praise for it. Is this something we just have to cope with? What about strangers at conferences asking you out for dinner during a poster presentation? Uncomfortable to say the least. Something we have to bear? I have once been told that I should apply for a professorship simply because I’m a woman and these days it’s super easy for women to get a position, basically everyone is accepted. I don’t think that’s acceptable and I wish I had been more assertive in this situation.

I don’t want to close on a negative note though. Thankfully, I had so many more positive encounters during the past years in academia than negative ones. Men and women who were genuinely interested in discussing research, appreciated my advise, gave me very valuable advice, motivated people – especially women – who were struggling and doubting themselves, facilitated socialising and networking at academic events, showed their own vulnerability and insecurities, shared their failures and how they overcame hurdles, educated themselves and were feminists. Let’s take them as an example.

Let’s try to be a bit more understanding, a bit more empathetic and a bit more supportive in this already stressful, fast-paced, competitive environment that academia mostly is. Let’s speak out clearly if we witness any kind of bullying, sexism and harassment. Of course things have to change on a much bigger scale and first and foremost systemically. But every one of us can make a difference – no matter how small – so let’s start today!

Recent Comments